About the author: William J. McGee is the Senior Fellow for Aviation & Travel at American Economic Liberties Project. An FAA-licensed aircraft dispatcher, he spent seven years in airline flight operations management and was Editor-in-Chief of Consumer Reports Travel Letter. He is the author of Attention All Passengers and teaches at Vaughn College of Aeronautics. There is more at www.economicliberties.us/william-mcgee/.

The nation’s air traffic control (ATC) system has been in the news frequently, and none of that news is good.

Controller shortages. Antiquated equipment. Near-misses due to runway incursions. And that was before things heated up over the last two months.

The United States has the world’s largest and busiest ATC network, covering 29 million square miles. For context, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) oversees 45,000 flights carrying 2.9 million passengers daily. At peak times there are 5,400 aircraft over American skies, some 10 million airline flights annually.

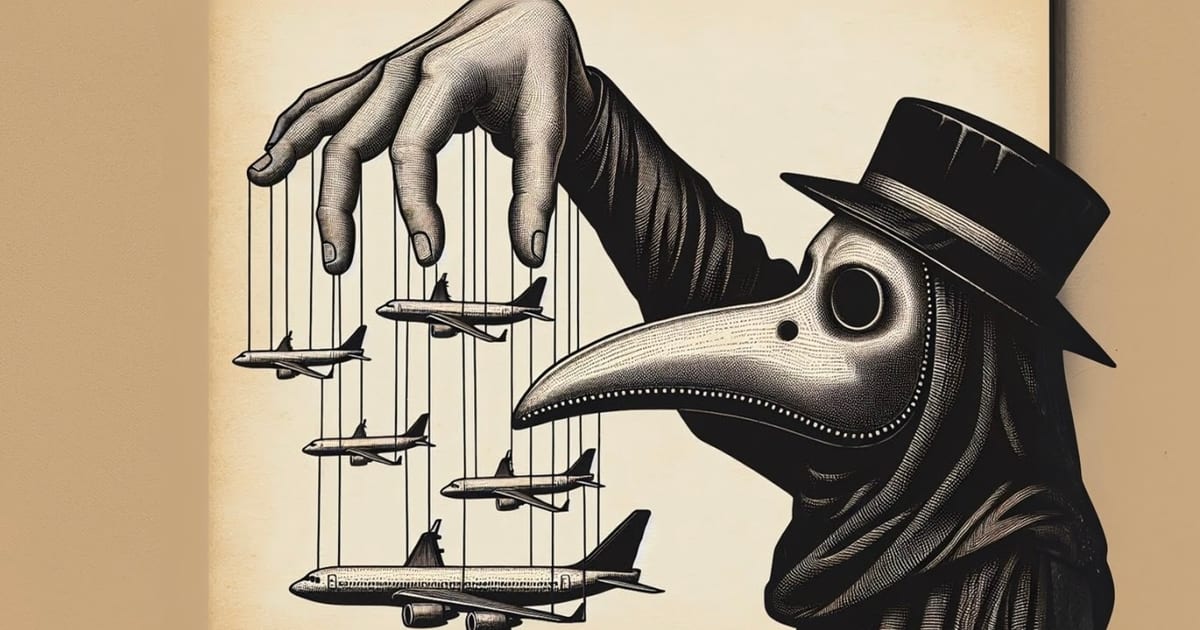

Theories abound about how to address all this.

But some cures are worse than the disease.

Last month I wrote here that U.S. aviation safety is under fire from within thanks to an administration that’s taking a chainsaw to government agencies.

Allow me to share some sensible solutions that are actually constructive, based on my decades of working with the industry’s best experts.

We do need more controllers; we do not need DOGE.

The U.S. has faced worker shortages in its airport control towers and regional en route facilities for many years now. This shortage has already led the FAA to take the unpleasant but necessary action of mandating that airlines reduce their flight schedules in certain regions, including New York City. No one wants to hear their vacation has been scrapped, but when you don’t have enough workers, alternatives aren’t an option.

How serious is this situation? A new FAA report entitled “The Air Traffic Controller Workforce Plan: 2024-2033” brings alarming facts:

• The FAA’s 2024 hiring goal was 8,966 controllers, but we fell short by 1,919.

• Among 313 facilities nationwide, a whopping 290 are understaffed.

• Controllers in Newark were moved to Philadelphia due to shortages.

These figures don’t account for normal attrition via quitting, retiring, or being fired, which makes near-term vacancies closer to 3,000 than to 2,000.

The Biden Administration had responded by ramping up hiring, meeting its 2023 goal of employing 1,500 controllers that year.

But that simply hasn’t been enough.

In contrast, Elon Musk’s “Department of Government Efficiency” (DOGE) cost-cutting strategy has slashed staffing, threatened controllers, and tasked overworked employees with meaningless “What I did this week” memos.

To be clear, no controllers have been axed yet by Musk’s team, but critical support staff and probationary employees that we cannot spare have. PASS, a union representing FAA employees, stated it was “troubled and disappointed.”

We do need more recruitment; we do not need racist, misogynistic scapegoating.

We actually do need robust FAA Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility programs so that we can help solve our staffing shortages by recruiting people who previously hadn’t considered aviation careers.

By attacking DEIA, Trump and Musk are shutting off the very pipelines that historically supply fresh talent.

As I noted here in January, DEIA is not about hiring or promoting people without skills and credentials, because the job requirements remain the same for everyone. It’s just about broadening efforts to entice new employees and undiscovered talent.

We’ve seen how the aviation industry has cut corners… The nation’s airspace is the last place where safety should be monetized for quarterly dividends.

We do need to modernize; we do not need to fight over cost.

Last month, two events brought ATC issues to light. One was a hearing before the House Aviation Subcommittee during which experts highlighted the woeful state of technology when it comes to operating the world’s most complex airspace.

That same day, the Government Accountability Office also released “FAA Actions Urgently Needed to Modernize Systems,” a new report spotlighting the FAA’s “reliance on numerous aging and unsustainable air traffic control systems.” GAO also criticized the Next Generation Air Transportation System (NextGen), which the FAA launched in 2004 and is still nowhere near implementation.

NextGen has become an aviation punchline, and some now call it “LastGen.”

Why has NextGen stalled? In 2010, I served as the consumer advocate on DOT Secretary Raymond LaHood’s Future of Aviation Advisory Committee, and I recall long arguments about—what else?—funding. Everyone agrees we need to upgrade ATC technology and thereby improve safety, efficiency, and profits, while also reducing carbon output. But even then, the airlines argued about the cost of modernizing aircraft for satellite-based technologies, so the full benefits of NextGen were stalled.

Enough. Many parties will benefit from upgrading our aging ATC system: passengers, corporations, airlines, airports, cities, states, regions, labor. It’s way past time to divvy up the cost between them.

We do need airlines to fix themselves; we do not need meltdowns.

There’s plenty of blame to go around for flight delays and cancellations. Consider how some U.S. carriers have melted down in recent years due to circumstances other airlines quickly rose above.

Whether it’s the snowstorms that grounded JetBlue in 2007 and Southwest in 2022, or the 2024 computer outage that paralyzed Delta, aging IT and/or inadequate crisis planning failed those passengers while other airlines recovered.

Just recently, United CEO Scott Kirby outlined his plan to fix ATC. However, it’s past time that both pot and kettle examine their own roles in this quagmire.

Simply put, there’s little benefit in “fixing” air traffic control if the airlines fail to fix their own internal messes.

In recent years I’ve had conversations with airline experts who are developing practical, immediate solutions for helping airlines streamline and expedite their flight operations.

We do need to examine FAA oversight; we do not need to to turn safety into profits.

Project 2025’s 922-page “Mandate for Leadership” addresses ATC and points out funding issues and technological gaps while stating as a goal: “Require the FAA to operate more like a business.”

Furthermore, it calls for digital/remote towers in place of staffed towers at airports. Much of this is from The Heritage Foundation, which has long advocated for privatizing ATC. In December, Reason Foundation called for user-funded ATC.

Such efforts have existed for years. But by 2017, the Congressional Research Service conducted a lengthy investigation that concluded “there does not appear to be conclusive evidence” that privatizing is either superior or inferior to government-run ATC (including FAA) for “productivity, cost-effectiveness, service quality, and safety and security.”

The CRS also defined two alternatives:

Corporatization would establish a wholly owned government corporation or quasi-governmental entity to oversee ATC. Corporatizing could entail forming a nonprofit model, as was recommended in 1993 by a national commission chaired by Vice President Gore. The United Kingdom and Switzerland both offer examples of corporatizing ATC without privatizing it into a for-profit model.

Privatization, on the other hand, would grant private ownership and control over an ATC corporation.

The real problem with privatization is that its advocates downplay two critical flaws:

Safety: In my view, if ATC is privatized, profit incentives will inevitably compromise safe operations in the name of “efficiency.” We’ve seen how the aviation industry has cut corners on everything from pilot training to aircraft maintenance outsourcing to quality assurance at Boeing. The very nature of “for profit” is to continually drive up revenues, and the nation’s airspace is the last place where safety should be monetized for quarterly dividends.

Competition: Any private model undoubtedly will allow the Big Four oligopoly—the airlines that control 80% market share—to assert power over smaller airlines.

There are plenty of things to fix in America’s ATC for the 21st Century.

We do need fresh approaches and collaboration on staffing, upgrading technology, and distributing costs.

We do not need chaos, downsizing, and more opportunities for corporations to line their pockets, starting with Elon Musk’s Starlink.